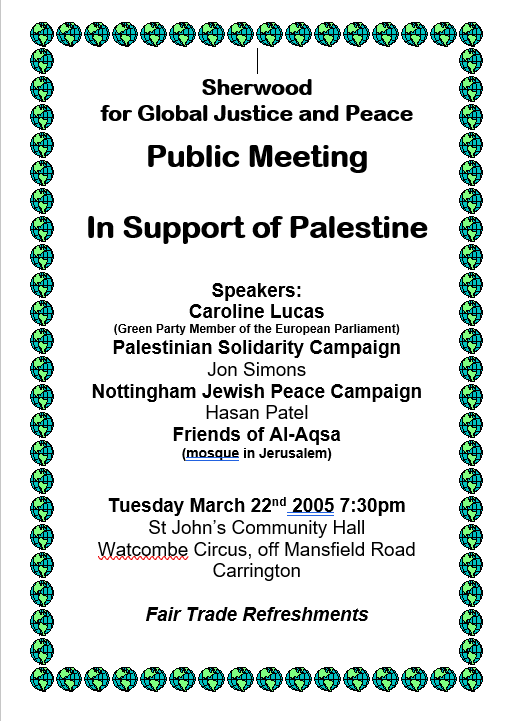

This blog is an extract from a draft of my autobiographical book about my life and Israel-Palestine. From 1995 – 2006 I lived in Nottingham, UK, where I taught at the University of Nottingham. I was active in the Nottingham Jewish Peace Campaign, from which developed a Muslim-Jewish dialogue group. Occasionally we were asked to provide speakers for events. A panel on ‘In Support of Palestine’ was organised in March 2005 by Sherwood for Global Justice and Peace. The other panel members were Caroline Lucas, then a member of the European Parliament for the Green Party, before becoming leader of that party and now its only MP. The other speaker was Hasan Patel from Friends of al-Aqsa, an organisation I knew little about, but neither I nor others in our group felt a need to check their credentials.

The text of my speech, which shows my adherence to a two-state solution at the time, included the following:

“What does it mean for a Jewish group, and in my case also an Israeli citizen, to be speaking in support of Palestine? It means above all that in spite of the conflict between two peoples over the same land, it is possible to support the best interests of the people of Israel while supporting the Palestinian people. It means that it is possible for the two peoples to make a historic compromise and share this small stretch of land between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River. It means that it is possible for the two peoples to live in peace. But it does not mean that compromise and getting to peace is easy.

To be Jewish and in support of Palestine means to be against the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. It means to believe in the self-determination of the Israeli people, and at the same time of the Palestinian people. It means that that the pull-out from Gaza and a few settlements in the northern West Bank can be only the first step, not a measure that can excuse the building of more new Jewish neighbourhoods to secure a ‘greater Jerusalem’. It means denying that the ideological Israeli settlers are today’s Zionist pioneers, denying that the removal of settlements is like the expulsion of Jews from Spain, and instead believing that the settlers are being returned home.

To be Jewish and in support of Palestine means recognising the enormous costs that the conflict has on both peoples. There is no need for altruism in acknowledging the costs born by the Palestinians, because there are so many costs for Israelis too. The huge military budget drains resources from social budgets, and compulsory military service weighs heavily on citizens, especially reserve duty, which has prompted hundreds of thousand of Israelis to leave the country. The conflict has also overshadowed ethnic relations within Israel. The children of Jewish immigrants to Israel from Arab countries grew up ashamed that their parents spoke the language of the enemy, losing the connection with the cultural heritage of their diaspora. Arab or Palestinian citizens of Israel feel they are treated as a fifth column, as second class citizens. The hatred that conflict brings has bred an endemic racism in Israel that shames the memory of the racism in Europe of which Jews were so recently victims. To be Jewish and in support of Palestine means not giving on the demand for security for Israel, but insisting that the only security that is meaningful is the security that comes with a just and lasting peace agreement.

To be Jewish and in support of Palestine means accepting that there are difficult choices ahead if peace is to be achieved. It means accepting that Israel does have responsibility for the flight of Palestinian refugees in 1948 and 1967, that the myths we were told about Israelis begging them to stay are precisely that, myths; that our great national leader Ben Gurion did order the expulsion of Palestinians from Lydda and Ramle during the 1948 war with a wave of his hand. It means acknowledging that the famous Zionist slogan from the early 20th century, ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ did a great injustice to the Palestinians in order to find a solution for Jewish homelessness. But it also means that homes for Palestinian refugees cannot be made in Israel at the cost of a new wave of homelessness for those who live now where there were once Palestinian villages and neighbourhoods. To be Jewish and in support of Palestine means accepting that Jerusalem, the city that is holy to Judaism, Islam and Christianity does not belong to one people, that its sites and ruins, its alleys and highways must be shared.

To be Jewish and in support of Palestine means to resolve the conflict while acting according to teachings of the great Jewish Rabbi Hillel, who lived and taught in Jerusalem in the years before the temple was destroyed by the Romans. He said:

‘If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

But if I am only for myself, who am I?

And if not know, then when?’

He also summarised the whole Jewish teaching, the Torah, as: ‘What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbour’. The Palestinians are our neighbours, so why do we do them what is hateful to us? It also means to understand the line from the Israeli national anthem, ‘To be a free people in our land’, means that we cannot be a free people in our land until the Palestinians are free in their land too. That’s what it means to be Jewish and in support of Palestine.”