Dear Natan,

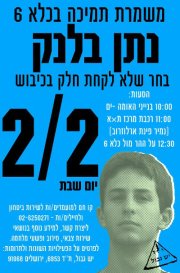

I am sorry that I cannot be with you in solidarity today on the hill opposite Atlit prison, taking part in the protest against your detention. I am far away in the Unites States, on a wintry, snowy day in Indiana, though rain or shine, I would much rather be spending my day with other activists on the buses organised by the refuser-group, Yesh Gvul, bringing you some moral support as you serve your fifth spell in military jail no. 6. Outside jail, the 20 days of this sentence, in addition to the previous four sentences since November 19, 2012, would slip by quickly. Inside, the time and boredom must weigh heavily on you. It takes a great deal of fortitude to be willing to serve one sentence after another, to persist in your refusal to serve in the Israeli armed forces. We have been privileged to read recently the intimate account by another conscientious objector, Moriel Rothman, of his spell in military jail. From afar, I can only admire your determination and commend the sacrifice you are willing to make for the sake of justice and peace.

I don’t know how much it helps you as you serve your sentence to imagine the people in Israel and beyond who want to give you their strength in support of your ethical stance. But in any case, let me say a little about myself. Some 18 years ago, as a (by then not so new) immigrant, I was inducted into the Israeli armed forces but refused to get on a bus taking us for basic training in the Occupied Territories. I, however, was lucky enough not to have to test my mettle for more than an hour, when an officer prompted me to come up with a personal problem so that I could stay at Tel Hashomer (the induction base) for another week. The same officer then released me until another induction date a few months later, and by the time that day came around I had found my first academic position in the UK and left Israel. It was hard enough to stand my ground for an hour in the car park in the face of various threats and cajolements: I don’t know what it feels like to persist and endure for more than 70 days.

Unlike myself, who grew up in Britain, for most of my teens in the warm environment of a Zionist youth movement, Habonim-Dror, you have had to find your way through the intensive socialization of the Israeli education system on the value and benefits of military service. More than that, you must have to contend with a huge amount of peer pressure, to toe the line, to do your duty to “defend” your country, to prove yourself as a man, to turn yourself into a “full” Israeli citizen, to take on your share of the burden that so many voices today clamor to share equally. In your refusal declaration, you show how clearly you see the blindness, denial, and even outright hypocrisy in all these statements about duty, defense and nationalism. As you say:

It is clear that the Netanyahu Government … is not interested in finding a solution to the existing situation, but rather in preserving it. From their point of view, there is nothing wrong with our initiating a “Cast Lead 2″ operation every three or four years … and we will prepare the ground for a new generation full of hatred on both sides. As … citizens and human beings, [we] have a moral duty to refuse to participate in this cynical game.

Somehow in your 19 year old wisdom you have already learned to see through the ingrained militarism of Israeli culture and society. You already practise the principles of New Profile, the feminist anti-militarism organisation that opposes the occupation, advocates the right of conscientious objection to military service, and supports you and other refusers practically. In their charter, they write that:

we refuse to go on raising our children to see enlistment as a supreme and overriding value. We want a fundamentally changed education system, for a truly democratic civic education, teaching the practice of peace and conflict resolution, rather than training children to enlist and accept warfare.

So, you do not see military service as a value, but instead have taken on another burden, another duty, an ethical duty to refuse to participate in the ongoing oppression and violence of the occupation.

But I do not share equally with you the burden of that duty. Nor when I was 19 could I see as clearly as you do now. No doubt at some point you will be – have been – called a coward. But you are braver than your conformist accusers. You will be told that you are naïve, a lover of your enemies. Yet, you are wiser than your detractors, the purveyors of hate. You will be told that you are a shirker, yet you have taken on a greater burden than any of those cogs in the machines of war and occupation. Thank you for your service.