The open day for the new building of Heaton Park Synagogue felt enlightening, literally. Before that, we had used a narrow, single story building with few windows, which must have been very crowded on high holy days. Aged six, I went with my family to marvel at the modern, tall structure. The front, including the doors, was made of glass that extended far above me, flooding the vestibule with light. Inside, the ceiling reached up two high storeys, above the tiered women’s section. Light streamed in through stained glass windows in the wall which housed the Holy Ark, where the scrolls of the Torah were kept. Then, in 1967, there was no fence between the synagogue and Middleton Road, only a low brick wall; no security guards, nothing to stop anyone from walking in. After services, people lingered to chatter in that open space, clearly visible from the street in our best clothes. I loved the slow, leisurely pace the congregants took on the way home, more than a few along the street where my family lived. These were the streets of our community, where we were safe, where we belonged.

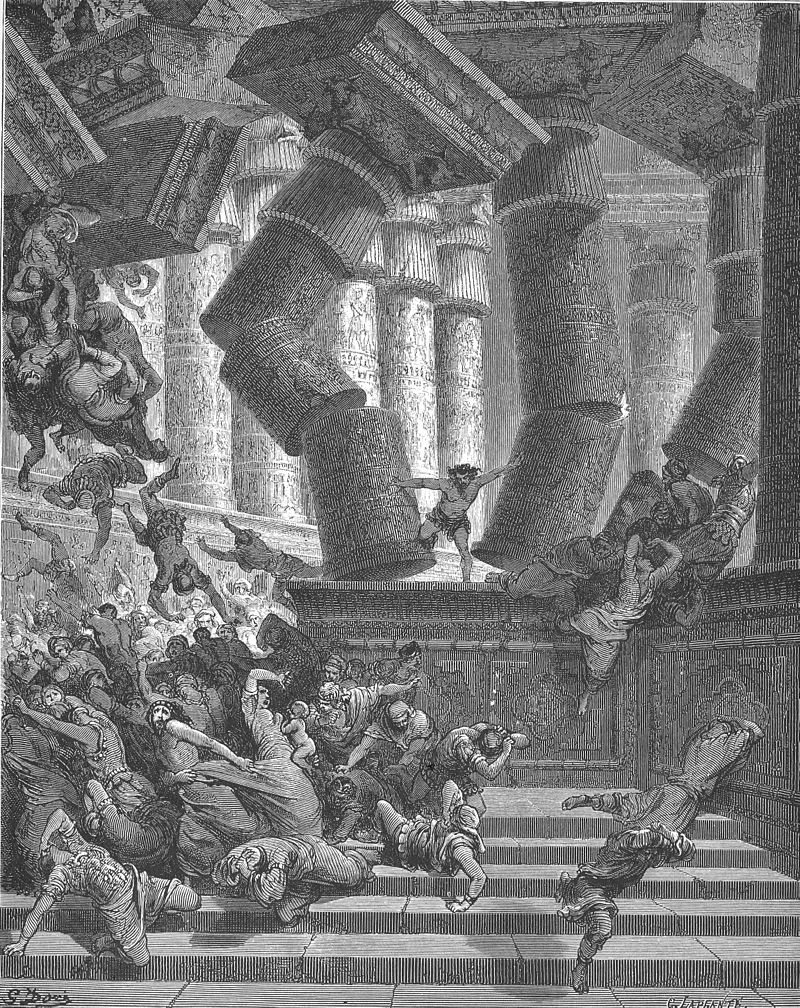

A few years after my Bar Mitzva at the Heaton Park synagogue in April 1974, I stopped attending altogether. My religious phase was over and so my connection to the congregation faded, other than through my parents who emigrated to Israel in 1982. (I followed them two years later but returned to the UK in 1995). But my roots in that congregation and my sense of belonging in that building have never been lost. So when I heard the news of the terror attack on Heaton Park on the morning of Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), it was as if the perpetrator, ‘pledged allegiance to Islamic State‘, had smashed the glass front of the synagogue and along with it the warmth of those memories. I did not recognise the names of the victims, Adrian Daulby and Melvin Cravitz, but then a cousin told me that Melvin had lived over the road from them as children and my brother thought he might have gone to King David’s school with him. This was an attack that struck close to home, too close.

But not all of my childhood memories of Heaton Park synagogue are wrapped with warmth. Inevitably, on Yom Kippur my thoughts go back to October 6th 1973, and my feelings touch the tender, pious twelve-year old I was then. I have blogged twice about that day on which Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel.

I should remember how tangible my worry was, how the terror of annihilation tasted dry like my fasting mouth, how the anxiety felt like my empty stomach. … Was Israel about to be destroyed? Were the Jews going to be thrown into the sea? Was this somehow God’s judgment? What sin had I or we committed that deserved such punishment?

About the Israeli experience of 1973 I wrote:

The trauma of October 6th 1973 mingles with the shock of Yom Kippur 2025, which mingles with the trauma of October 7th 2023. So, what to do with the trauma, the fear, the shock, the loss, the deep sense of vulnerability?

For the generation of Israelis who fought the war, their fear gave way not to despondency but to anger at the ineptitude and negligence of the country’s leaders. While for some the Labour establishment remained the focus of their frustration, others came to understand that as citizens they could no longer trust their government to do what is best for Israel. Following President Sadat’s visit to Israel in 1977, a group of the ‘1973 generation’ wrote to then Prime Minister Begin in the famous ‘officers’ letter’ to argue for a path of peace rather than settlements, and the Peace Now movement was born.

Today more than one generation of Israelis have felt the losses of the failure in 2023 to conceive of and anticipate Hamas’ attack, and more than one generation will feel the consequences of the vengeful, genocidal response of Israel’s civil and military leadership, the damage to Israel’s reputation and the brutalization of its society that led it to perpetrate a second Nakba. And today Israelis do not need to wait several years for the activists who know that they cannot rely on their government. There are all those who, despite their government’s stupidity and stubbornness, campaigned for two years in Israel for a deal to exchange the hostages for Palestinian prisoners, which they knew meant ending the war, some of whom have set up Kumu (Arise), a movement for national renewal. There are those who already knew on or before October 7th that there should be no war, such as the Arab-Jewish Hadash party and the Jewish-Palestinian Standing Together grassroots movement.

But what about we Jews in the UK? What do we do with our trauma? Jonathan Freedland wrote about “Jews wanting to huddle against the cold, to be among those to whom they do not have constantly to justify or explain themselves.” Emma Barnett, also once a young member of the congregation, felt in the immediate aftermath of the attack that she was ” left with myself and to confront how I choose to respond. … I don’t feel much like being virtuous. While Jews have been fearful for a long time as antisemitic attacks and vandalism ramp up around the world, an attack at a UK synagogue represents a threshold being crossed in this country.” Rachel Cunliffe focused on the context since October 7th:

The actions of a country 3,000 miles away of which I am not a citizen have left me feeling unwelcome in the place I was born. Pick a side. The isolating irony is that I can’t. Two years ago, I was blissfully ambivalent about the need for a Jewish state, a haven of last resort for a diaspora persecuted through the centuries. Now that I’ve seen how a significant portion of the country I think of as home really feels about the Jews, it seems more necessary than ever, even as that haven descends into darkness.

I have felt all of those things too, from upset that all the Manchester synagogues had to be evacuated on Yom Kippur 2025, even though it is decades since I have been to a Yom Kippur service; to wondering if I would be allowed in if I rushed round to huddle with Jews at my local synagogue; to feeling like going to settle in one of the kibbutzim overrun by Hamas on October 7 2023. Like Rachel Cunliffe, I have felt pressure to pick a side, which I have resisted through activism with UK Friends of Standing Together which grieves for both Israeli victims of Hamas’ October 7th massacre and Palestinian victims of Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza. Those are comforting feelings, but do they confront the trauma?

Perhaps a better path is indicated by Hadash and Standing Together in Israel, an activist path of solidarity and partnership across national, religious and ethnic boundaries. It will not be straightforward. Many UK Muslims might be repelled by the knowledge that two thirds of UK Jews identify as Zionists, until they hear from us that it does not mean we support Israel’s conduct in Gaza, but the principle of a state of refuge from antisemitism. We Jews will have much to learn too, about the extent and depth of Islamophobia, from which we are not immune. Perhaps, then, rather than huddling alone we could huddle together with one of the traumatized victims of the Islamophobic arson attack on the mosque in Peacehaven who has not left his home since? In Nottingham, I can huddle with volunteers at the Salaam Shalom kitchen, a Muslim-Jewish charity project. And we could huddle with the Manchester Council of Mosques, which declared:

Our thoughts and prayers are with the victims, their families and the Jewish community at this distressing time… Any attempt to divide us through violence or hatred will fail – we remain united in our commitment to peace and mutual respect… It is vital at moments like these that we stand together as one Manchester – united against hatred and committed to peace, justice and respect for all.

Such expressions of solidarity does not in itself tackle the trauma, but it is a step towards active solidarity that can. And yes, that statement describes a Manchester and British community where I would happily walk the streets, feel safe, and belong.